Record Records - Part 5, Cricket-I: Warne and Murali

Sporting achievements that will probably never be repeated or bettered, an opinion

Scrutinising sport is a funny thing. It’s a competition of physical prowess, mental toughness, team work, preparation, all that jazz that coaches go on about. But it’s hard to put a number on mental toughness, hard to precisely define how prepared an athlete is, hard to objectively state the team work at play. But we want to know these things! The inherent nature of competition drives the desire to quantify who is competing the best, and those really invested in the culture and fabric of a sport know that winning titles and medals doesn’t always reflect this. And so we get statistics, analytics, numbers based solely on output and production by the athletes, an imperfect but inescapable surrogate for what we really want.

This series is a celebration of those in their sports that have statistical achievements so impressive I don’t think they’re likely to ever be bettered or even repeated. This is by no means supposed to fulfil some perfect list of the most impressive records and statistics across the sporting world, these are just records that are interesting and incredible in my opinion, and are therefore of course very much centred on the sports that I love or pay attention to. This series of articles is focused on sports that I am attached to, so, apologies for inevitably missing some incredible record in a field I’m ignorant of.

After a little break we’re back and moving on to a new code. Cricket. If you thought I had the tendency to lapse into story mode in previous weeks, well, buckle up.

If you want to revisit the previous examinations of other incredible sporting achievements but in an American setting:

To hear the breakdown of Jerry Rice and his records, as well as an introduction to statistics in American football, see the first part of this series.

To explore the incredible career of Tom Brady, see the second part of this series.

To get an introduction to basketball statistics and then journey through the remarkable career of Bill Russell, see the third part of this series.

To hear the story of the awe inspiring Wilt Chamberlain, see the fourth part of this series.

But this week we’re leaving North America behind and crossing the ocean, well, oceans, today’s focus is phenomenally popular in all directions outside the Americas. So, let’s talk about…

Cricket

Are there any sports more associated with statistical obsession than the world’s most popular bat and ball codes? Cricket and baseball, both iconic for being boring (to the uninitiated) and dry, the latter referring to an obsession with statistics. Biased as I am, I would argue that the original of the two takes the cake (I’m talking the stats thing, but some would argue the boring part too…). Of all the sports I love, cricket is the one where every discussion on players, every analysis shown by the broadcast, every biography and documentary, every aspect of the game focuses on the numbers. For the uninitiated, there are three forms of cricket played at the professional level at a huge scale, and these are:

First class cricket, the original form, typically played over three to five days, called test cricket when played internationally

One day cricket, which when played between nations are called one day internationals (ODIs), typically played over 7 to 8 hours

Twenty-twenty cricket (T20), a format supposed to compress and provide more excitement, also played internationally (T20Is), typically played over 3 to 4 hours

The player statistics that are most valued by teams and eager fans vary between the formats, where the shorter forms encourage attacking aspects of the game at the expense of stamina or totals, while the middle length is somewhat of a compromise between the two. For example, in test cricket a batter is valued for scoring lots of runs, regardless of how long they take (usually), whereas in T20 a team would rather a player who scored 30 runs very quickly instead of 60 runs sluggishly.

Now, for the really uninitiated, I recommend this guide.

Once we understand the basics of the game we can talk numbers. The key statistics recorded are:

For batting:

Runs scored

Balls faced (deliveries)

Times dismissed

Minutes at the crease

Boundaries hit (when a batter hits a ball to the boundary of the field it is worth more runs)

And from those base stats additional ones are calculated or tallied:

Number of times accumulating 50 or more runs, 100+, 150+, 200+, etc.

Runs scored per balls faced (strike rate)

Runs scored per times dismissed (batting average)

For bowling:

Balls bowled

Wickets taken

Runs allowed

Sundries (no-balls and wides, there are strict ways a player can bowl the ball, if they do it wrong the opposition gets a free run, called a sundry or extra, and they have to bowl the delivery again)

And from those stats more are calculated again:

Runs per wicket taken (bowling average)

Runs per over bowled (economy)

Wickets taken per balls bowled (also called strike rate)

Number of times accumulating 5+ or 10+ wickets in an innings, or 10+ in a match

There are also statistics recorded of the bowling (or fielding) team not specific to the bowler:

Catches

Stumpings

Extras (some are associated with the bowler, others with the keeper and fielders)

There are also other things recorded like types of dismissal, but we’ve covered the core stats.

Cricket is the most popular summer sport in the world, thanks largely to India, but it is an acquired taste. My fruitless repeated attempts to convert the love of my life/best friend to watch cricket with me demonstrates that it is possible to be an amazing person and not enjoy the sport, so, I won’t judge you too harshly if it’s not your cup of tea. Still, if you’re not a cricket fan (and especially if you are), I hope the following pieces are somewhat interesting even if the value of the statistics discussed is lost.

To start with we’re going to be delving into the strangely parallel careers of…

Murali and Warne - Career Bowling

The GOATs of spin. Image taken from here

Cricket is a batters’ game. The rules have almost consistently changed to accommodate them over their bowling peers. Most countries’ lists of all-time great cricketers are loaded with batters, with the very best bowlers added to the mix from time to time. After all, the team that scores the most runs wins, so surely the batters are the most important? Well, an old adage of cricket disagrees, saying that “bowlers win matches, batters determine the margin”. A good bowler restricts the opponents’ batters from scoring said runs, and even better dismisses them, as a batter once out can’t score any more runs. But one good bowler isn’t enough, you need an elite bowling team to ensure the pressure is maintained. Whereas one good batter is often enough, where a huge score from the star player can carry the team.

This is one of the key reasons batters get more of the spotlight, they can shine more individually. But, if we go back to that idea of best cricketers by nation, there are two countries that have their best bowler right near the top, or in some opinions, at the top. Muthiah Muralidaran of Sri Lanka, and Shane Warne of Australia; Murali and Warnie. These names are for Sri Lanka and Australia what Lionel Messi and Michael Jordan are for Argentina and the USA. Murali and Warnie didn’t just dominate in the game (though they certainly did as we will see), but also had remarkable cultural impact throughout and after their careers.

I’m presenting these two legends together because their careers overlapped so closely, and their achievements are so remarkably comparable. Warne played his first test match for Australia in January of 1992, at the SCG, aged 22. Murali played his first test match for Sri Lanka in August of the same year, at the Khettarama Stadium against Warne and Australia, aged 20. Warne played his last test match in January of 2007, also at the SCG, then aged 37. Murali however played a few more years, his last test coming in July of 2010, at the Galle International Stadium, aged 38. Throughout their careers Warne played 145 test matches, Murali 133, the 12 test match deficit present despite playing longer and missing fewer tests. This is a symptom of the more prominent test playing nations playing more tests overall. Murali more than made up for this in the shorter forms of the game, playing 350 ODIs to Warne’s 194.

Their career start, end, and total matches weren’t the only things they had in common. Each was a spin bowler, the variety of bowling that until they played lacked the fame and impact of fast bowling. The earliest bowling legends were all pacers, Lohman and Barnes for England, Turner for Australia, and then of course the superstar bowlers of the 70s and 80s were renowned for their speed, Thompson and Lillee for Australia; Ambrose, Walsh, Marshall, Holding for the West Indies, Akram and Younis for Pakistan. Spin bowling has been a big factor in cricket since forever, but it wasn’t traditionally the most dominant or impressive form. In fact, before 1990 the number of bowlers with 300+ test wickets was 9, of which only 1 was a spin bowler, Lance Gibbs of the West Indies. Since then, the number has ballooned to 37 in total, including 9 spinners. In other words, the century of test cricket before 1990 saw 9 bowlers crack 300 wickets, with 11% spinners, and the 30 years since has seen 28 bowlers reach the mark, with 29% spinners. This means the spinning legends are from the same two generations. Check out the career spans of the spin bowlers who have 300+ test wickets:

Then if we make it 400+ Gibbs and Vettori drop off, and we’re left with only three countries that have produced spinners with 400 or more wickets, and they’ve all produced more than one. If we make it 500+ wickets, those three counties keep one spinner each, all playing at the same time: Kumble, Warne, and Murali. Shift the bar to 700+ and only Warne and Murali remain:

That final picture doesn’t change if we add fast bowlers either. Only two guys in the history of test cricket to crack 700 wickets, regardless of bowling style, and their careers were simultaneous. That said, at time of writing Jimmy Anderson is only 10 wickets shy of the 700 threshold, which if he gets there it will make him the first fast bowler to do so. Of course his career has spanned 20 years, as opposed to the 15 and 18 for Warnie and Murali.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves, discussing total wickets already, I just wanted to illustrate two interesting points via those timelines. First, the fascinating coincidence that the two (by a long shot) best spinners of all time played in the exact same period. And second, the incredible rise of dominant spin bowlers after the advent of Kumble, Warne, and Murali, especially the latter two.

Back to 1992, (amazing year by the way) and the start of Warne’s and Murali’s test careers. Neither set the world on fire straight away, Warnie in particular took a while to get going. Over his first 4 tests he only took 4 wickets, at an average of 96, though three of those came in a single innings against Murali’s Sri Lanka that won the game for Australia. In his 5th test however, his first Boxing Day Test at the MCG, he took 8 wickets at an average of 14. He had middling success after that before the truly stunning Ashes tour of the UK in 1993, where he was the leading wicket taker of the series for either side (only a year into his career). From then on he was it, continually one of the best bowlers for Australia or indeed the whole world. That year he ended with 73 wickets, the most in history for a spin bowler in a calendar year (at that point). Murali started a bit stronger, his first 4 tests yielded 16 wickets at an average of 34. But thanks to the cruel nature of test cricket, where the big dogs play a lot more tests, Murali would only play 6 tests in 1993, compared to Warne’s 16, how could he possibly take 73 wickets (or more, ideally) with less than half as many opportunities?

Regardless, within a year of their debuts the two bowlers were indispensable to their respective teams. Warne’s early career was phenomenal, operating at bowling averages usually reserved for the most accurate of pace bowlers. Generally, spinners are feast or famine, in that to spin the ball their action yields a delivery much slower. For example, a standard quick bowler will deliver each ball at approximately 135 to 145 km/h, whereas spinners almost never crack 100, often operating in the 80 to 90 km/h range. This means if they don’t get enough spin or movement off the pitch it is much easier for the batter to play the slower ball. That’s what I mean by feast or famine, it’s very difficult for a spinner to bowl prolonged spells of dangerous, spinning balls. There’s almost always a few easy shots for the batter to put away, keep the runs ticking over, and ease the pressure. This is one reason why spinners traditionally have higher bowling averages than most fast bowlers. Warnie in the mid 90s was not a traditional spinner. From 1993 to 1997 (inclusive), Warne took 277 wickets at an average of 23.31. To put that into perspective, Dennis Lillee, one of the greatest bowlers in Australian cricket history, took 355 wickets at an average of 23.92, over his entire 13 year career! Warne took almost 78% as many wickets as the great Lillee in only 5 calendar years, and operating at a tighter average. Astonishing.

Image taken from here

Warne’s average would slip a little as his career progressed, the next five full years he played he took a very similar 272 wickets, but this time at an average of 27.01, though this included the year he returned from a one year ban. Warne was tested with a banned substance in his urine, a diuretic. He claimed it was just a “fluid tablet” his mother had given him to help his appearance, but a committee found him guilty of breaching the Australian Cricket Board drug code and he was banned for a year. After that he actually improved at the end of his career, unlike most athletes, his last two years accounting for another 147 wickets at an average of 25.07. At time of retirement he had the most wickets in history by any bowler, 708, at an average of 25.42. The greatest spinner before him, Anil Kumble of India, had amassed 619 (13% less) at an average of 29.65. Absolutely amazing. But Warne’s record would not stand.

Murali was forever chasing Warne’s career numbers, again, because Sri Lanka just didn’t have the pull (and still don’t) to play as many tests as Australia. When Warne retired in January of 2007, he had played 145 test matches. At the same moment in time, Murali had played 108, or one quarter less, despite debuting in the same year. That said, his prolific wicket taking meant he was never far behind the Aussie, even pulling ahead during Warne’s enforced year away from tests. He was the first to break Ambrose’s then record number of wickets in a career of 520 in 2004, though Warne would in turn take the record himself later the same year, which he would hold until he retired thanks to playing more tests per year. But Murali kept playing long after Warne retired, taking back the record for most career wickets 11 months after Warne’s last match. Murali retired in 2010 at the age of 38, a year older than Warne at his retirement. As he debuted younger, not to mention Warne was banned for a year, Murali played three more years than Warne. Despite this, he ended up playing 133 tests, 12 less. But those missing tests didn’t matter, he took 800 wickets, 92 more than Warne.

Unlike Warne, Murali’s test average steadily improved his entire career, which is truly incredible. I haven’t checked, but would be shocked if any other bowler in the top 10 list had the same phenomenon. When he took his 300th test wicket, his career average was 25.18, not shabby, though Warne’s average upon the same milestone was 23.56. When Murali eclipsed Ambrose for most wickets of all time his average had improved radically, to 22.89. When Warne took the record for himself a few months later, his career average had held more or less steady, 25.59. When Warne became the first bowler to take 700 wickets, his average was 25.36, impressively consistent since his 300th. But when Murali took his 700th wicket his average was now 21.33! He would retire with a slightly higher number, but his ability to take wickets (and lots) without giving away runs is truly stunning for a spin bowler. Indeed, of the top 10 wicket takers in test history, only Glenn McGrath has a better average, and he was renowned for his accuracy and difficulty to score off, and he took an astonishing 237 less wickets than Murali, despite playing more test innings.

ODIs are a different kettle of fish, with Sri Lanka able to organise and play as many as the bigger test nations. Over their careers Warne would prioritise tests, but still play 194 ODIs. Murali on the other hand played 350! That’s the 9th most by any player by the way. In his 194, Warne took 293 wickets at a very comparable average to his test career, 25.73 compared to 25.41. This is impressive given the difficulty in keeping runs low in the shorter versions of the game. Murali in his 350 ODIs took 534 wickets, and again with a staggeringly low average for the format, at 23.08. These totals mean, when combined with their test matches, each of these legendary spinners took over 1000 wickets for their country, a feat no-one before or since has achieved. Again, at time of writing James Anderson is getting close, he needs another 23 wickets for England (tests or ODIs) to join this very rare club. That said, it would be safe money to bet he’s played his last ODI, and 23 more wickets in tests is no gimmee at his age.

Murali and Warne both debuted the same year, both retired the most prolific wicket taker in the history of international cricket at the time, both won a world cup, and both had strangely fairy-tale like endings. When Warne announced his retirement, he had 699 test wickets, and 992 international wickets. He took his 700th test wicket in his penultimate test, and his 1000th international wicket in his final test. When Murali announced his retirement, he had 792 wickets. In his last test match he took another career five-wicket innings (he has the most of course, we’ll get to that), and needed 3 more in the second innings to reach 800. The first 2 came, but then others contributed and India were suddenly 9 wickets down, Murali needed the last one to get his 800th wicket. But storm clouds were coming in, India were trying to play out the draw on the last day of the test, Sri Lanka needed the wicket from someone so it wasn’t like they were idly bowling pies from the other end to give Murali time to get the milestone. But, with his last ball of the last over of his last test match he got it, finishing with the insane record of 800 test wickets. It would be too sickly trite even for a Hollywood ending, but it happened.

Image taken from here

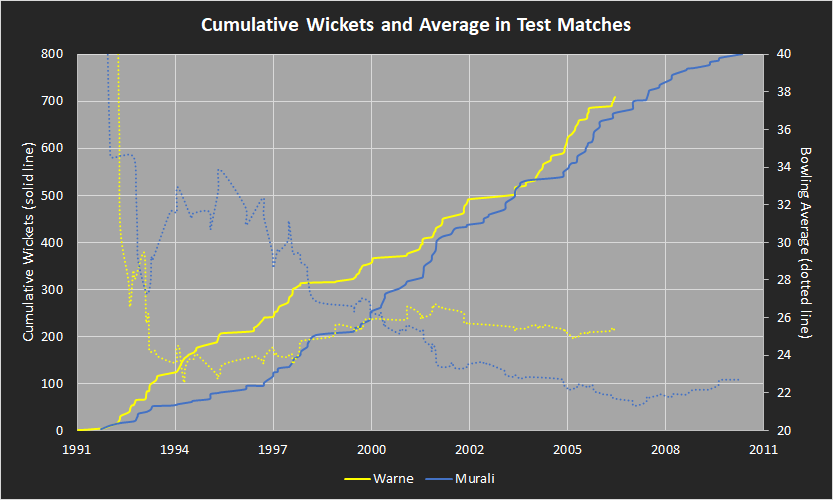

What I’m trying to say is how uncannily similar the two cricketers careers were, at least on the pitch. They were incredibly different men off of it, but their bowling journeys are remarkable. Check out their cumulative wickets in tests, ODIs, and then combined. The graphs are a little confusing at first because of the dotted lines, which is their career bowling average over the same time period. Remember, a lower average is better.

You can see the upward inflection after Murali’s first few years, it really is amazing that he caught up during Warne’s ban despite playing so few tests per year before that. Also, watch the dotted blue line, that’s Murali’s average, and that trend is truly insane.

Similar story to the tests, though a lot more graph for Murali…

This is the summation of the previous two graphs. The far greater number of ODIs helps Murali stay in touch and then stay in front of Warne for total wickets, even if he had to wait for Warne to retire to take the test wicket crown.

However, with all of the content so far, there is a caveat a lot of Murali haters bring up. And that’s the high number of tests and ODIs played against minnows. This is a term used in cricket to refer to nations outside the traditional power houses of the sport, the big fish if you will. Sri Lanka themselves are borderline minnows in tests, especially outside of Sri Lanka, and were certainly so in all formats before Murali. Two other nations that have sporadic success but lack a Murali of their own and have perennially been called minnows are Zimbabwe and Bangladesh. The geographical proximity helps explain why Murali played more tests against the latter, but the former comes down to two cricketing nations that want to play but aren’t getting games against the big fish. I must admit I was surprised just how much Murali played against Zimbabwe. Of his 133 tests, 11 were against Bangladesh and 14 against Zimbabwe. For Shane Warne, of his 145 tests, only 2 were against Bangladesh, and a solitary 1 game against Zimbabwe. In ODIs, for Murali it’s 17 v BAN and 31 v ZIM, while for Warne it’s 2 v BAN and 12 v ZIM. In total, over their international careers, Murali and Warne faced Bangladesh 28 and 4 times respectively, and Zimbabwe 45 and 13 times respectively. Combined, it’s 73 against 17. The argument goes that Warne spent most of his career up against the strongest teams in the world, while Murali played a large portion of his games against weaker sides, and so of course he took more wickets and at a better average. But let’s look at each of those graphs from above, but after removing all matches involving Bangladesh or Zimbabwe.

Obviously we expect the totals to go down, but it’s pretty nuts how far below Murali is in terms of total wickets. He still boasts the better test average though. Excluding those opponents, the two legends’ test figures are: Warne, 691 wickets at 25.41; Murali, 613 wickets at 25.05. Murali loses 187 of his wickets by excluding those two minnows, and his average jumps from 22.73. But what about including the shorter forms of the game?

I mean, Murali played so many ODIs, so taking away those countries doesn’t really change the picture so much. Excluding those opponents, the two legends test figures are: Warne, 268 wickets at 26.19; Murali, 444 wickets at 24.61. Murali loses 90 of his wickets by excluding those minnows, and his average increases, but not as drastically, from 23.01. Looking at total international wickets then:

This is the interesting one. By excluding those countries Warne no longer joins the 1000 wicket club, while Murali does. Murali also retains bowling average bragging rights. I think it’s an interesting argument to be sure, but not one that robs Murali of his prestige. Besides, it’s not his fault who his country was able to schedule matches against, you’ve got to play what’s in front of you. That said, Murali’s average against the two best teams of his generation, Australia and India, is over 32. But wait, Warne’s average against India is 47! So get stuffed critics, Murali is awesome.

Although, while we’re talking about critics of Murali, we need to address the biggest controversy of his career. One that dogged him throughout his illustrious and incredibly productive span. That is his bowling action. In cricket, you must bowl the ball, not throw it. If your bowling action involves a bent arm it must stay bent, you can’t straighten your arm as in a throw. Murali was born with a congenital defect in his arm, this meant his shoulder and wrist bent differently. With this, Murali was able to generate incredible spin using a variety of different delivery styles that all boggled the mind. He had been accused of illegal deliveries earlier in his career, but it really came to a head when he toured Australia in 1995-96. In the Melbourne Boxing Day test he was called for a no-ball by the umpire several times for illegally straightening his arm. It happened again during an ODI at Brisbane a week later. The International Cricket Council reviewed the incident and declared Murali’s action legal. Despite this, on the next tour of Australia in 1998-99 he was again called for no-balls by the same umpire as that 1996 ODI in Brisbane. The Sri Lankan team were in uproar and nearly abandoned the match, the captain even received a fine for his actions later. However, Murali underwent a study and was again cleared. “At no stage was Muralitharan requested to change or remodel his action, by the ICC”. Throughout both tours the atmosphere was much more hostile than is usual from Australian fans, with Murali taking a lot of verbal abuse.

At this point Murali had two different types of delivery at his disposal, but not long after he developed a third, the infamous “Doosra”. This proved very difficult for batters to play, and even more than the earlier styles had the appearance of straightening his arm. He submitted to a bunch of tests, and they found that the Doosra delivery involved a straightening of 10-15°, while at the time the ICC had a limit of 5°. However, after the analysis of other bowlers of the era, bowlers who never had such claims against them like Murali, it was seen that bowlers around the world typically had a straightening of around 10°, with many cracking 15° like Murali. In the end the ICC reviewed their own stance and Murali was allowed to continue bowling all of his different styles.

Still, there were unconvinced critics. So, to put the issue to rest Murali agreed to bowl wearing an arm-brace in front of a cricket audience and with many of his vocal critics in attendance. The brace was tried on by some of the witnesses (including critics) who all agreed that straightening your arm while wearing it was impossible. Murali proceeded to bowl his three different styles of delivery as usual. He then put on the arm brace and repeated the exact same deliveries. The ball lost a bit of air speed due to the extra weight on his arm, but the measured degree of rotation, how much spin he got, differed negligibly. It’s reported that:

“With the brace on, there still appeared to be a jerk in his action. When studying the film at varying speeds, it still appeared as if he straightened his arm, even though the brace makes it impossible to do so. His unique shoulder rotation and amazing wrist action seem to create the illusion that he straightens his arm”

Many of his most vocal critics were converted by these displays as well as the biomechanical testing of a range of bowlers. Michael Holding, who had been very vocal against Murali and was on the ICC panel conducting the study into Murali and regulations on bowling in general said:

"The scientific evidence is overwhelming ... When bowlers who to the naked eye look to have pure actions are thoroughly analysed with the sophisticated technology now in place, they are likely to be shown as straightening their arm by 11 and in some cases 12 degrees. Under a strict interpretation of the Law, these players are breaking the rules. The game needs to deal with this reality and make its judgement as to how it accommodates this fact."

Image taken from here

So let’s talk stats.

We’ve gone through the comparisons between Warne and Murali, but we haven’t dug deep enough into how remarkable they are compared to other bowlers. So, let’s look at who has the most test match wickets:

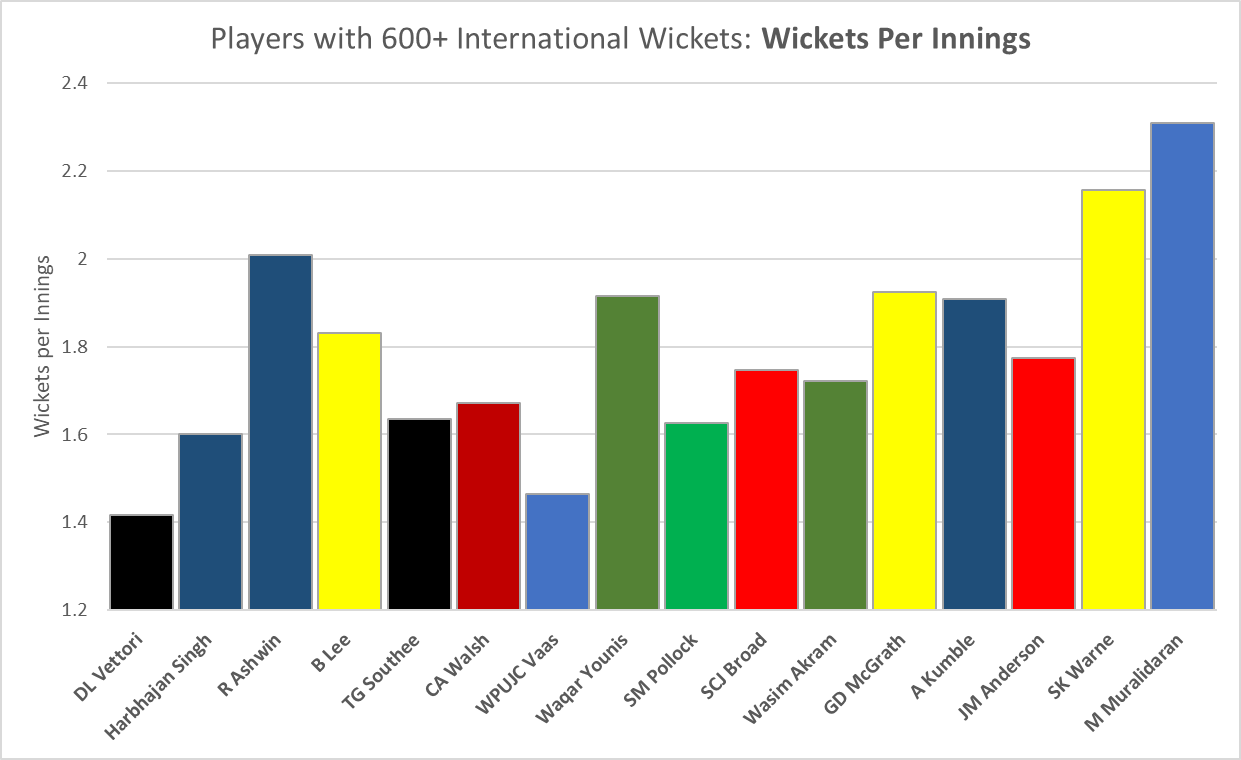

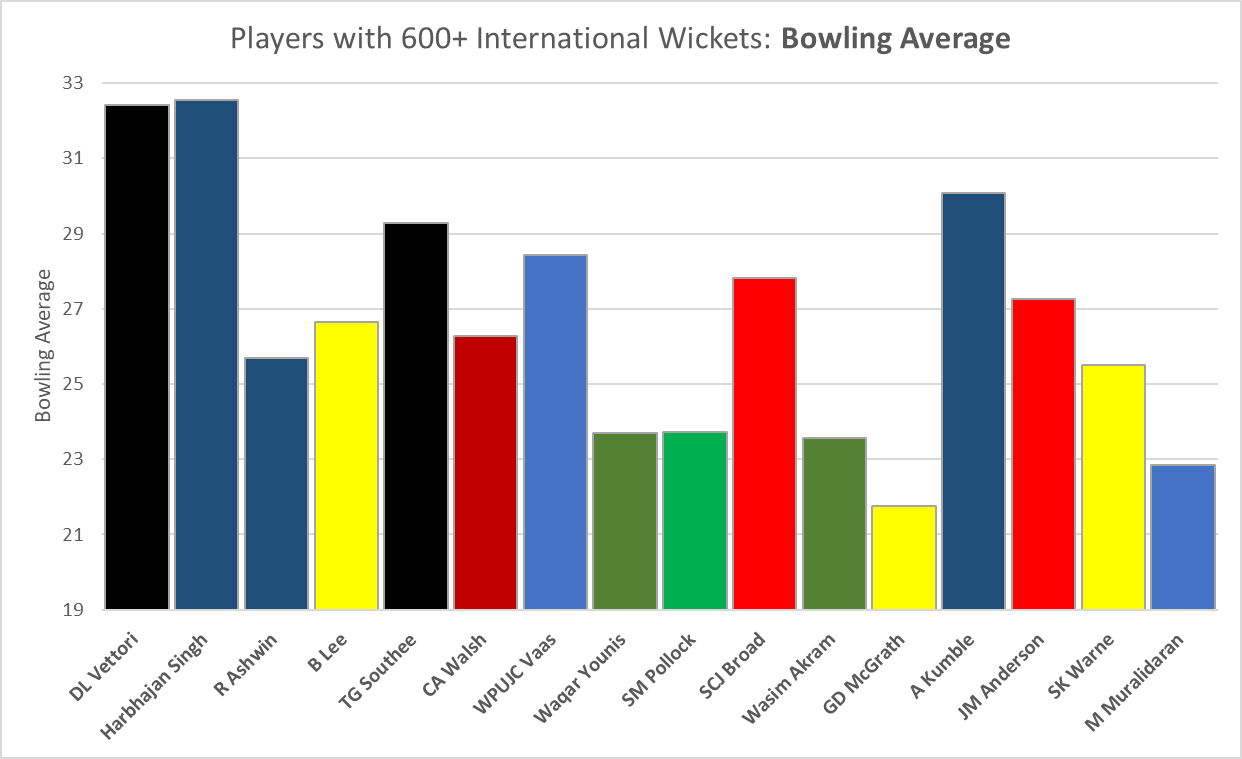

Murali way out in front. That right there ladies and gentlemen is what we call an unbreakable record. Jimmy Andseron, currently third, has played for 20 years and still can’t catch Warnie, let alone the gulf to Murali. But, what about the quality of bowling? For that we turn to bowling average and wickets per innings. For the latter a big number is good, like the totals above, but when it comes to average, remember that a lower number is better as it means you get wickets for less runs conceded. On that, also remember that on the whole spinners have worse averages than fast bowlers. I’m going to present the same line-up of bowlers as the graph below but adjusted for the new statistics.

Wow. The wickets per innings one is particularly flattering to Murali, but the bowling average one is also insane. For a spin bowler to have an average less than 23 while also taking the most wickets in history, it beggars belief. Warne isn’t too bad in either category also. The other interesting trend is how reliant Broad and Anderson have been on volume, or years played. Both have atrocious wickets per innings and pretty crappy bowling averages for fast bowlers.

Now, let’s look at the same plots but include ODIs, remember that Murali played a crap-load of ODIs, including a disproportionate number against minnows.

Hahaha, oh boy, and we thought the test match wickets record was unbreakable. Let’s compare average and per innings again:

In the wickets per innings plot Warne is a lot closer to Murali, but the average is again insane. To only be beaten by McGrath for average while taking over 1300 wickets when the next best barely cracked 1000, it really is mental. But, let’s also check out economy, because if you’re not taking wickets you should at least be restricting runs:

Again, Murali shines. Warne very tidy too though, economy under 3 from a career of tests and ODIs? Very impressive.

The other milestone bowlers aspire to is 5 wicket hauls, taking 5 or more wickets in an innings is a relatively rare feat. Of that graph above for example, McGrath and Anderson have 29 and 32 each, out of 243 and 341 innings respectively. That means for each innings McGrath and Anderson bowled there was a 11.9% and 9.4% chance respectively they would take 5+ wickets. For Warne it’s 13.6%, but for Murali, well that number is 29.1%!!!

That graph is strictly for test matches by the way.

Boy howdy that’s a crazy figure, and again, an absolutely unbreakable record for Murali. Bowlers also accumulate 10 wicket matches, where across both innings of a test they combine for 10 wickets. Looking at McGrath and Anderson again, they each managed that feat 3 times, McGrath from 124 tests, Anderson from 183, or for a given test they played, they took 10+ wickets over the match 2.4% and 1.6% of the time respectively. Warne however managed it for 6.9% of matches, but for Murali, it’s 16.5%!

And again, of course, this is unbreakable.

Finally, in the history of international cricket (test matches, ODIs, T20s) a player has taken 8 wickets in an innings a total of 101 times. 60 of those were by players who would never do it a second time. 13 players managed to do it twice in their career, 2 players did it thrice, while 1 player has done it 4 times. That player is George Lohman. Murali of course has done it more, cracking 8 wickets in an innings a record 5 times.

Keep in mind that Barnes and Lohmann, 2nd and 3rd on the list, played in the very early days of test cricket, when batters had toothpicks for bats and pitches were left uncovered which led to wild unpredictability of bounce and turn. The only modern bowler in shouting distance of Murali is Kapil Dev with 3, but again, I’m pretty convinced that 5 innings of 8 or more wickets is unbreakable also.

This section has been pretty heavy on the Murali love, so what records does Warnie hold?

Well, these ones:

Most test wickets in a calendar year - 96, second place is Murali with 90

Most consecutive ODIs with 4+ wickets - 3, tied with 13 others

Most international (and test for that matter) runs without a century - 4,172, second place is 3,439

And that’s it. He’s part of a lot of exclusive lists, like players with over 1000 runs and 100 wickets, but he doesn’t have that many career records anymore. He had a bunch when he retired, but Murali came along and took them all:

Most test match wickets, Warne 2nd

Most ODI wickets

Most international wickets, Warne 2nd

Most 5 wicket innings in tests, Warne 2nd

Most 10 wicket matches in tests, Warne 2nd,

Most balls bowled in test matches, Warne 3rd

Most maiden overs (no runs) in test matches, Warne 2nd

Fastest to 350, 400, 500, 600, and 700 test match wickets

Most international wickets in a calendar year - 136, Murali 2nd as well, Warne 3rd

So yeah, Murali has a lot of records that will stand the test of time, many of which would be Warne’s if Murali had never played. However, there is one clear aspect of their careers that Warne gets the rub over Murali:

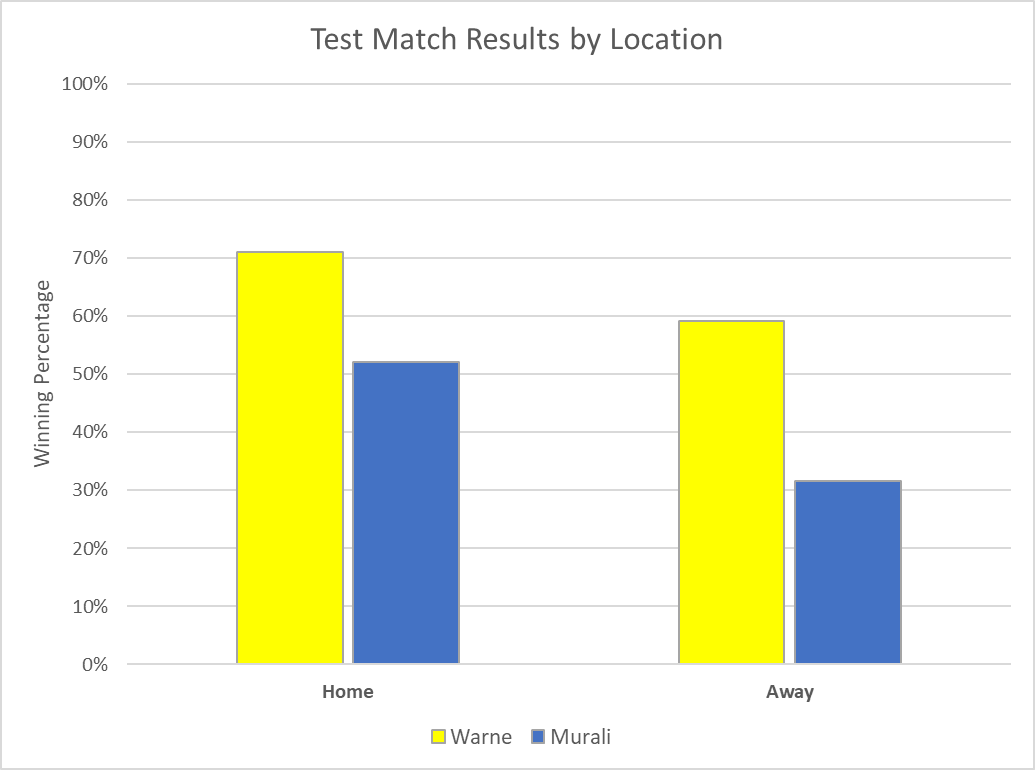

Throughout his career Shane Warne would have a winning record against every single test team, the worst one being a 52.6% win-rate against the West Indies. This is all the more astonishing in test cricket, where many matches result in a draw. To win more than half your tests against every opponent is insane. Murali on the other hand had winning records against Zimbabwe, Bangladesh, and exactly 50% against New Zealand and the West Indies. Against the powerhouses of cricket however his wins were scarce. Against Australia particularly so, only managing 1 win out of 13 test matches. The other thing of note is how one-sided Murali’s record is due to this dominance at home, where the familiar conditions and renowned turn of Sri Lankan pitches helped immensely:

Warne’s winning percentage at home of over 70% is proper insane for cricket. But even his away record is phenomenal, winning over half of the tests played on tour. Murali by comparison has a decent home record, nearly 60% win rate, but it plummets to just over 30% on the road.

These stats however aren’t due to the players themselves, both were match winners, but it’s more a reflection of the truly incredible Australian test side of the late 1990s and early 2000s. If anything, the Murali numbers need more context. You see, before he debuted in 1992 Sri Lanka had never beaten Australia in a test match, or England, or New Zealand, or South Africa, in fact never won a test match outside of Sri Lanka. But by the time he retired they had beaten every team that plays tests, had won test match series at home against every nation, and won test match series on tour, in England, New Zealand, and Pakistan; and of course Bangladesh and Zimbabwe, who Murali never lost to. In ODIs, they had never won a series outside Sri Lanka before Murali debuted, but less than 4 years later they won the World Cup! Fittingly it was over Australia, who’s vitriolic hosting of Murali the year before started the whole bowling action controversy. It also fits the narrative of this article that Murali should deny Warne another piece of legacy.

Image taken from here

But will the records ever fall?

There are several records held by Warne or Murali, and lots held by Murali where Warne is number 2, that will never be broken, or even have the number 2 supplanted. A key factor in this is the change in international cricket focus. ODIs slowly took on importance during the careers of these greats, and were added to by T20s. These days most test playing nations are playing less test matches than they have for generations. Playing style has also changed due to the influence of the shorter formats. All in all player career totals are decreasing compared to the legends of the 1990s and 2000s. These records are almost sure to never be broken due to a combination of the insane production/talent of the eponymous bowlers and the changing nature of international cricket:

Most test wickets in a calendar year (Warne followed by Murali)

Most test wickets in a career (Murali followed by Warne)

Most test 5-wicket innings (Murali followed by Warne)

Most test 10 wicket matches (Murali followed by Warne)

Most test 8+ wicket innings (Murali)

I do think James Anderson will crack the 700 test wicket mark, he only needs 10 more, but he might not crack Warne’s total of 708, and will never get close to Murali’s 800. But if he does he will almost certainly be the last to join the 700 club.

Then, you’d think the change towards shorter formats would help players catch up with the total international records, but the problem is that there are generally less wickets taken during ODIs and T20s compared to tests. So these records are also unbreakable:

Most international wickets in a calendar year (Murali followed by Murali)

Most international wickets in a career (Murali followed by Warne)

Most international balls bowled in a career (Murali)

After retirement, Murali has had stints in coaching, including a notable period with the Australian team. Murali has said that having the team that was so against him call on him to coach was a big victory in his career. He has also had numerous philanthropic endeavours, particularly focussed on welfare to southern Sri Lanka. It’s worth noting here the context of Sri Lankan cricket. Sri Lanka has a troubled past, and for the second half of the 20th century saw decades of internal strife and widespread violence. The success of the cricket team of the 90s, in large part due to Murali, was one of the few unifying forces for the country. For this reason, not to mention being the best bowler in history, Murali has such a strong cultural impact for his nation.

Warne on the other hand did not unify a nation. We have delved into Murali’s controversy, over his throwing action, but barely touched Warne’s. There was that brief description of the reason for his one year ban, but for those in-tune with cricket, or just living in Australia in the late 90s and the 2000s, Warnie was an absolute character, a modern avatar of Australian larrikinism. He attracted controversy and headlines, and was a dividing figure in terms of how he and the Australian cricket team were viewed. On the pitch he was amazing, as we’ve seen, one of the very best to ever play; but his antics outside of the game were certainly polarising. His cultural impact was his larger than life presence in the media, and his incredible talent, emblematic of an historically dominant cricket team. Regardless of one’s view of him though, he certainly didn’t shy away from who he was, never tried to be who others thought he should be, and lived his life his way. He died in 2022 from a heart attack, aged only 52.

It will take a radical shift in international cricket focus, as well as another all-time prodigy to challenge the career numbers of these true legends of the game. In the end, the kings of spin will reign on top of the bowling records for a very, very long time.

This feels a little contrived, but I love it. Taken from here

Alright then, let’s finish with some highlights

Here are a few of Warne’s many, many wickets for Australia (the first one in the video is the famous “ball of the century” in his first Ashes tour that really put the young leg spinner on the global stage):

Video sourced from here and here

And here are a few of Murali’s even more numerous wickets for Sri Lanka:

Video sourced from here

Thanks for reading beautiful people, next time we’ll be staying with cricket, see you then, or maybe before… (that came out more ominous than intended)