The outlier of all sporting outliers, we had to have Bradman eventually, strap yourself in for a bumper edition of stats and stories.

Scrutinising sport is a funny thing. It’s a competition of physical prowess, mental toughness, team work, preparation, all that jazz that coaches go on about. But it’s hard to put a number on mental toughness, hard to precisely define how prepared an athlete is, hard to objectively state the team work at play. But we want to know these things! The inherent nature of competition drives the desire to quantify who is competing the best, and those really invested in the culture and fabric of a sport know that winning titles and medals doesn’t always reflect this. And so we get statistics, analytics, numbers based solely on output and production by the athletes, an imperfect but inescapable surrogate for what we really want.

This series is a celebration of those in their sports that have statistical achievements so impressive I don’t think they’re likely to ever be bettered or even repeated. This is by no means supposed to fulfil some perfect list of the most impressive records and statistics across the sporting world, these are just records that are interesting and incredible in my opinion, and are therefore of course very much centred on the sports that I love or pay attention to. This series of articles is focused on sports that I am attached to, so, apologies for inevitably missing some incredible record in a field I’m ignorant of.

We’re back again for more record records, and this time finally turning our attention to the most record-y of all records, the batting of Donald Bradman.

For other articles in this series, so far we’ve covered:

the many records of Tom Brady

the incredible feats of Wilt Chamberlain

and most recently we had an intro to cricket stats and the parallel achievements of Shane Warne and Muthiah Muralidaran

Now it’s time for the biggest article yet, with more graphs and stats than you can poke a cricket bat at. I tried to keep the bio section short because the records section is huge. But it’s fitting that it’s huge, after all, no-one else in all of sports has as impressive a resume of records than:

Don Bradman - Test Cricket Batting

The statistical outlier above all other statistical outliers in sport, the Don. Image taken from here

At the start of 2018 an Australian cricketer, Steve Smith, was at the end of a purple patch rarely seen in test cricket. In the prior 4 calendar years, 2014-2015-2016-2017, Steve Smith had piled on 5004 runs at an average of 75.82. By comparison, most players are considered truly great batters if they retire with an average above 50, and, in the history of the game only 14 players have managed to score 10,000 or more runs in their entire career. Smith scored half that number in only 4 years! What’s even more amazing was that his numbers weren’t inflated by home test match drubbings, as most cricketers tend to have drastically different returns of form between batting at home or away. Smith in that period however had scored almost half of those runs on the road, and his away average for that span was 62.13!

At the culmination of this prolific period Smith had an ICC test batting rating of 947, where the ranking system is a sum of points gained based on the recent performances of the batter and the strength of their opposition for these matches. Typically the number one player in the world in any given week has a rating in the high 800s, sometimes low 900s. For reference, Sachin Tendulkar’s career high was 898, Steve Waugh’s 895, Brian Lara 911. Smith’s ranking of 947 broke the record for the 2nd highest of all time. That “2nd” component is important.

Smith was on top of the world in terms of test cricket. But for all his success he wasn’t given the same titles of other dominant athletes of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. He wasn’t called the GOAT, like Michael Jordan, Serena Williams or Tom Brady, or “the Greatest” like Muhmmad Ali; he wasn’t labelled “the King”, like LeBron James or Wally Lewis; not even something abstract like “Megatron” (Calvin Johnson), “Nobody” (John Eales), or “the Dream” (Hakeem Olujawon). No, the moniker Smith was anointed with by the media was, “the Best Since Bradman”.

I knew when I started this project delving into impressive sporting records that Bradman would be chief amongst them. But because his achievements are just so remarkable, and so famously remarkable, I didn’t want to cover the story straight away. But then again, to not get to him within the first few pieces would look a little like I was deliberately avoiding the subject, so here we are.

The outlier of all outliers is Bradman’s career test batting average. My father has a favourite anecdote, where as a young boy I asked him: “Dad, how good was Bradman really?”. To which he replied: “Well, most batsmen don’t finish their careers with an average above 50, and there’s only a few in the 60s. There’s none in the 70s, none in the 80s, but Bradman, he averaged 99.94.” How did he know off the top of his head such an obscure multi-decimal number as 99.94? I thought in my naivety. As I would come to appreciate, this particular number is one of the most famous numbers in the Australian consciousness, one because of the quirk of it being just a hair below 100, and two, because it is so, so far ahead of anyone else to ever play the game.

A great example of this is illustrated in the wonderful book “Instant Cricket Library, an Imagined Anthology” (2018) by the legendary Dan Liebke, where he presents snippets from a wide range of if-only-they-were-real cricket books. One of these is “Mathematics for under-14 cricketers”, where he opens with a hilarious and illustrative question regarding the Don:

Photo taken by myself, from Instant Cricket Library pg 113, 2018, Dan Liebke

I thought it would be fun to work through these together. Now, keep in mind that great batters don’t usually get many ducks (that’s when you’re out without scoring a run for those cricket noobs amongst you), and to score a lot in a row is very rare. For example Steve Smith has scored 9 ducks in his 100+ test match career, and never in consecutive innings. Also remember that a batting average of 59.9 would still be the 5th best batting average in history

a) Average = Runs/Dismissals

New Average = Runs/(Dismissals + 10)

New Average = 6996/(70+10) = 87.45

So if zombie Bradman resumed his career with 10 consecutive ducks he would still have a career average more than 50% higher than the 2nd best of all time.

b) Average = Runs/Dismissals

New Average = Runs/(Dismissals + 20)

New Average = 6996/(70+20) = 77.73

Alright, now he’s had 20 consecutive ducks and his average is still miles ahead of the rest of the batters in history.

c) Average = Runs/Dismissals

60 = 6996/(70 + x)

70 + x = 6996/60

x = 46.6 ~ 47

Hahahaha. So Bradman, who only played 80 innings in his career, would need to resume his zombie career with FORTY SEVEN STRAIGHT DUCKS for his average to drop below 60 and settle for 5th best of all time.

d) Average = Runs/Dismissals

50 = 6996/(70 + x)

70 + x = 6996/50

x = 69.92 ~ 70

This is insane. If he scored nothing at all for 70 straight innings he would still have a test average better than:

Virat Kohli (49.29)

Michael Clarke (49.10)

Virender Sehwag (49.34)

e) It’s already well past ridiculous Mr Liebke, point well made!

But before we go deeper into the lunacy of Bradman’s stats, let's talk about the man himself.

Donald George Bradman grew up in regional Australia. Born in Cootamundra (only a few hours down the road from where I’m writing this) he moved to Bowral at the age of two and half. Both country towns now have Bradman museums. Donald’s mother, Emily Bradman, played cricket for NSW in an intercolonial competition, bowling left-arm spin, and her brother George Whatman, Don Bradman’s uncle, captained the Bowral men’s cricket team, so it’s fair to say there was cricket in the familial waters growing up.

It was as a young boy in Bowral that Bradman became obsessed with batting, and we get the legendary story of him practising with a single stump and a golf ball on the curved wall that formed the base of the house’s water tank. The curved surface meant the golf ball would come back at him from all angles, and with the practice bat being as slender as the ball itself, his incessant practice provides a wonderful story and mind's eye image. It is the mythical origin story that a legend of folklore needs. This legend would start playing cricket as soon as he could, scoring his first century as a 12 year old playing school cricket. That same year his father took him on a trip to Sydney (130 km) to the famous cricket ground of the same name, the SCG, to watch the original test cricketing nations continue the oldest international rivalry in sports, England v Australia, fighting over the Ashes. Here we get another mythical-esque story, where the young Donald says to his father while watching the game:

“I shall never be satisfied until I play on this ground”

By the way, obviously he would go on to play (and a lot) at the SCG, but later, after he retired, one of the SCGs seating sections was named “the Sir Donald Bradman Stand”. So he didn’t just get his wish to play on the ground, his legacy partakes in every game.

Bradman illustrating for an article the curved water tank where he practised batting as a child with a single stump and a golf ball. Image taken from here.

He left school at aged 14 to follow his sporting ambitions, and after two years pursuing tennis instead, returned to cricket at aged 17 playing for the Bowral team. He quickly became a regular selection, and in his first season got the attention of the big smoke, with Sydney newspapers reporting on his remarkable achievements, a 17 year old scoring 234 and 320 not out. The following year, after a crop of ageing Australian test players retired after a losing Ashes series, the NSW cricket association held “Country Week” tournaments where players were invited to participate. At 18, his performances during this tournament earned him an invitation to play in the big leagues, to join the St George grade cricket side. He made a century on debut (because of course), and by the end of the season was named to the state 2nd side. The very next season he made his first class debut, playing for the NSW state team at 19 years old. Again, a century on debut (he can’t bloody help himself) and then later in the season his first century at the SCG, that ground he was so determined to play at. The rapid rise of “the Boy from Bowral” was remarkable, but he was overlooked for the Australian side selected to tour New Zealand.

Deciding he’d be more likely to improve and be selected if he wasn’t travelling the 130 km from Bowral to the SCG every week he moved to Sydney before the next Ashes tour kicked off. In the first match of the state tournament, the Sheffield Shield, he scored a century in both innings, and then when NSW played the English touring side he scored 87 and 132 not out. With such a run of form he could no longer be overlooked, and was selected for the first test of the Ashes, making his test match debut in Brisbane at the age of 20 in only his 10th first class game. Unfortunately he broke his streak of century making debuts, as he and the entire Australian line-up were rolled for 66 in the second innings to give England a result of winning by an innings and 675 runs, which by the way is still an unbeaten record in tests. He himself only contributed 18 and 1 in the two innings and was dropped to 12th man for the second test. But, following an injury, he played in the third and thankfully remembered that he’s Don Bradman and that he should be scoring centuries, scoring 79 and 112 in the two innings. He briefly became the youngest player to score a test century, but that record only lasted a week, a lot shorter than many of his records would prove to last…

His heroics were insufficient though, the Australian side was at an ebb in its prowess (I mean obviously, all out for 66 in the first test) and they only managed to win the 5th and final test of the series. In the 4th test Bradman was looking in touch again when he was run out. He clearly didn’t like the experience as it never happened again in the remaining 20 years of his career! In the 5th test he scored another century in the first innings, and was partner to the captain in the 2nd when the skipper hit the winning runs to salvage some pride from the series.

Across the 4 tests he played he scored 468 runs at an average of 67, despite the atrocious performance in the first (by himself and the rest of the team). Those aren’t setting the world on fire results, but still, they’re the sort of numbers that modern batters, in the peak of their powers, would be more than happy with from a 4 test series, and very impressive for a first ever test series. Then, in the following domestic season his form really accelerated, he broke the record for highest score at the SCG with his first double century, then scored 124 and 225 in a trial match to select players to tour England, and then broke the world record for any form of cricket, scoring 452 not out against Queensland. Damn.

Don Bradman in the year of his test debut, 1928, aged 20. Picture taken from here

He was of course selected to tour England in 1930, though there were some critics who didn’t like his self-taught, “bush cricket” batting technique despite his production. It didn’t have the flourish that many wanted from the gentlemen’s game. Bradman continually developed his technique throughout his career and that with his sheer production silenced all critics pretty quickly. The tour went very well for Bradman and Australia. Following their drubbing at home a few years earlier Australia were not fancied to do well on the return trip, and sure enough they lost the first test despite another Bradman century. The second test however Bradman scored a whopping 254, and Australia won to level the series. But this was nothing compared to the third test. Coming in at number 3 on the first day of the test he scored a century before lunch, then another century between lunch and tea, and at stumps was on 309*. Today, more than 90 years later, still no other player has achieved the feat of 300+ runs in a day’s play. He went on to break the record for most runs in a test innings, dismissed for 334, he was still only 22 years old. Unfortunately (well, fortune for England) rain intervened and the test was a draw. The fourth test was also a rain affected draw. In the fifth and deciding test he made another double century, 232, as Australia won the test and reclaimed the Ashes.

I’ll let Wikipedia explain the significance of this feat to those back home:

The victory made an impact in Australia. With the economy sliding toward depression and unemployment rapidly rising, the country found solace in sporting triumph. The story of a self-taught 22-year-old from the bush who set a series of records against the old rival made Bradman a national hero. The statistics he achieved on the tour, especially in the Test matches, broke records for the day and some have stood the test of time. In all, Bradman scored 974 runs at an average of 139.14 during the Test series, with four centuries, including two double hundreds and a triple. As of 2023, no-one has matched or exceeded 974 runs or three double centuries in one Test series

And this was just his second ever test series! After playing only 9 test matches he was a national icon, and despite not wanting the spotlight, for the rest of his life he would be one of the most famous people in Australia, and world wide in cricketing countries. His next few series were not as astounding as that English tour but still dominant, before the infamous Bodyline tour of the 1932-33 Ashes in Australia. This saw the English develop an approach specifically designed to counter Bradman. Which is fair enough, when a 22 year old rocks up to your door and drops the most runs in history (and that would stand forever as the most runs in history…) on you to shockingly regain the Ashes, you’re going to want to do something about it. But what they did was controversial because it was such a negative and cynical tactic, this approach was termed bodyline. It essentially involved consistently bowling fast deliveries targeting the batters body, not their stumps, and expecting them to create catching chances in their desperate attempts to defend themselves. It caused a lot of uproar, and had very vocal critics around the cricketing world, and not just the Australians at the receiving end of it. It was viewed as intimidating and aggressive, and against the sportsmanship that cricket prided itself on. It worked though, Bradman only averaged 56.57 for the series (compared to his career average of 112.3 before the series…) and England regained the Ashes, but the tensions it caused even threatened the diplomatic relations between Australia and England. A famous line from early in the series came from the Australian captain (Bill Woodfull) rebuking an English player for attempting to apologise between sessions following a few Australian players receiving blows to the body:

“there are two teams out there and only one of them is playing cricket”

Which I just love, has cinematic drama all over it. Following the series international cricket moved to eliminate bodyline tactics from the game, first via requesting captains in the domestic and international scenes to ensure the game was played in the correct sporting spirit, and then when this proved ineffective they empowered umpires to identify and stop what was called “direct attack” bowling.

Well, we’ve probably gone a little deeper into his early test series than I intended, but that’s because his career started so incredibly. The thing is, his career never stopped being incredible, but we don’t have time to go through the whole shebang with as much detail as we have so far. Suffice to say that he was not a flash in the pan early career wonder, his form continued (his career average never dropped below 90) and he was made the Australian captain in 1936, though there had been some drama before that we won’t cover here (player politics). Then, after playing test cricket for 10 years, including 35 test matches for a return of 5093 runs at an average of 97.94, World War 2 broke out. Bradman joined the Royal Australian Air Force before transferring to the Army, but saw no combat for either due to chronic muscle problems diagnosed as fibrositis. He was eventually invalidated out of service due to health issues, and he spent the rest of the war recuperating. When international cricket resumed it was doubtful he would be able to play, and while he did take time to ease back into it on the domestic scene, by the time England toured Australia for the 1946-47 Ashes he was the Don again, playing all 5 tests and scoring 680 runs at an average of 97 including a century and a double century. The next home summer India toured Australia for the first time and a now 39 year old Bradman scored 715 runs across five tests at an average of 178.8 against the touring Indian side. On the eve of the fifth test he announced that it would be his last in Australia, but that he would still tour England in 1948 as his last test series.

That tour has gone down in history as Bradman’s Invincibles. Across every tour match and all the England v Australia tests they were undefeated, the only time in history. This included a ridiculous chase in the 4th test when Australia were set a world record 404 in the 4th innings, which Bradman chased down with 175 personally, winning with 15 minutes to spare on the last day. His last test culminated with one of the more enduring tales of his career. Before the test he had 6996 runs, and had been dismissed 69 times. If he scored only 4 runs he would have 7000, then even if dismissed he would still have a career average of more than 100. Instead he was out for a duck on the second ball he faced! And, as there was no second innings due to an English batting collapse, Bradman had to settle for that famous average of 99.94. Following this final series batting for Australia against the old foe, a British cricketer and writer (RC Robertson-Glasgow) wrote of the English reaction:

"... a miracle has been removed from among us. So must ancient Italy have felt when she heard of the death of Hannibal"

And while I admire the poetry of the sentiment, I don’t love the analogy, after all Hannibal lost the war despite his individual brilliance, while Bradman ended his “war” with an undefeated campaign of astonishing accomplishment. He partook in 8 Ashes series, winning 5, losing 2 and one drawn series (though the draw meant Australia retained the Ashes).

The invincibles, captain bradman is middle front row. Picture taken from here

He was knighted following his retirement, the only Australian cricketer to ever receive the honour. Sir Donald Bradman accepted offers to travel with and write about the Australian cricket team, published a memoir, and had many prominent roles on company boards before in later years taking on significant duties within the administration of Australian cricket. He was a figure of myth and legend in his own lifetime, few sporting icons (or anyone really) see multiple museums open in their honour, have multiple sporting stands and grounds named after them, a military naval vessel named after them, and featured on stamps while they live. Indeed, he became the first living Australian ever to appear on a postage stamp. There are so many great stories about Bradman that people love to tell. One of my favourites comes from an article in the Independent (the UK, think Trent Crimm from Ted Lasso):

On his visits to the Adelaide Oval Bradman occasionally frequented the Australian dressing room. On one such visit in the late '80s Australia were being beaten up rather badly by the West Indies. Malcolm Marshall, Curtley Ambrose, Courtney Walsh and Patrick Patterson were running riot and at the end of day's play Bradman sat down in the dressing room to have a cold beer with the team. Dean Jones, the Australian middle-order batsman, asked Bradman how he would have fared against this great West Indies attack. Bradman indicated that he would probably have averaged 60 or 70 against them. The admission took Jones and his Australian team-mates by surprise. Sixty or seventy, that wasn't a lot for The Don? But before anybody had the chance to speak Bradman said: "But I am 80 years old now."

Another great one comes from Bat, Ball & Field, 2022, by Jon Hotten. In this book there is a story of the great Australian fast bowler, Jeff Thomson, who wasn’t just fast, but blisteringly fast, regarded as one of (if not the) fastest bowlers in the history of cricket. He was attending a backyard BBQ on the rest day of a test match (that used to be a thing) and the Don happened to be there also. Thomson was hitting his straps as a test bowler, was at the peak of his raw pace powers, Don Bradman on the other hand was 70 years old. Some kids managed to convince the great man to face a few deliveries, and when some older lads got involved but couldn’t get him out Thomson joined in too:

“I thought this won’t take long – this little old guy with glasses. I thought I had just better bowl my legspinners as it wouldn’t look too good in the newspaper if I killed Don Bradman in a game of backyard cricket. Bradman had nothing but a bat ... no protector, no pads or anything on a green turf wicket. I thought ‘Good luck old man you will be dead shortly’. He just belted the first ball and I thought ‘Hmm that wasn’t a bad shot, it must have been luck’. I bowled one more ball and then sat aside and watched this guy for 20 minutes flog two young bowlers. If you had Greg Chappell, Viv Richards or Ian Chappell in there they would have been backing away because they had no protective gear. But Bradman just backed himself to hit everything and I was gobsmacked.’’

The next day Thommo arrived at the Australian cricket team dressing room demanding to know why Bradman wasn’t still playing for Australia!

There are many stories like this, because Don Bradman is a part of Australian legend, he’s national folklore, despite playing in the most recent century he’s treated like a myth from a bygone age. He was never one for the spotlight himself, indeed his character throughout his life was reclusive, interpreted by many of his team mates as aloof. He was described as a complex but driven man, not quick to close relationships but possessing strong principles. At the inauguration of the Sports Australia Hall of Fame in 1985, Bradman said (as one of the 120 initial inductees):

“When considering the stature of an athlete or for that matter any person, I set great store in certain qualities which I believe to be essential in addition to skill. They are that the person conducts his or her life with dignity, with integrity, courage, and perhaps most of all, with modesty. These virtues are totally compatible with pride, ambition, and competitiveness.”

Don Bradman had a history of complicated relationships with those close to him, especially team-mates, but also his family. His son, John, changed his last surname to Bradsen in 1972 when he was 33, finding the Bradman name a burden. They would grow closer later in life and John did change his name back to Bradman and has been the spokesperson of the family and their estate since his father’s death in February 2001 aged 92. The memorial service was attended by every big name in cricket, as well as multiple Australian ex-prime ministers (and the prime minister at the time). He was a legend and a myth in his own life-time, and his stature has only grown since as his achievements continue to prove utterly unparalleled.

Speaking of, let’s back to the stats.

His most impressive statistic, batting average, truly is stunning. Look at the all time batting average chart (for players who have played a minimum of 20 tests):

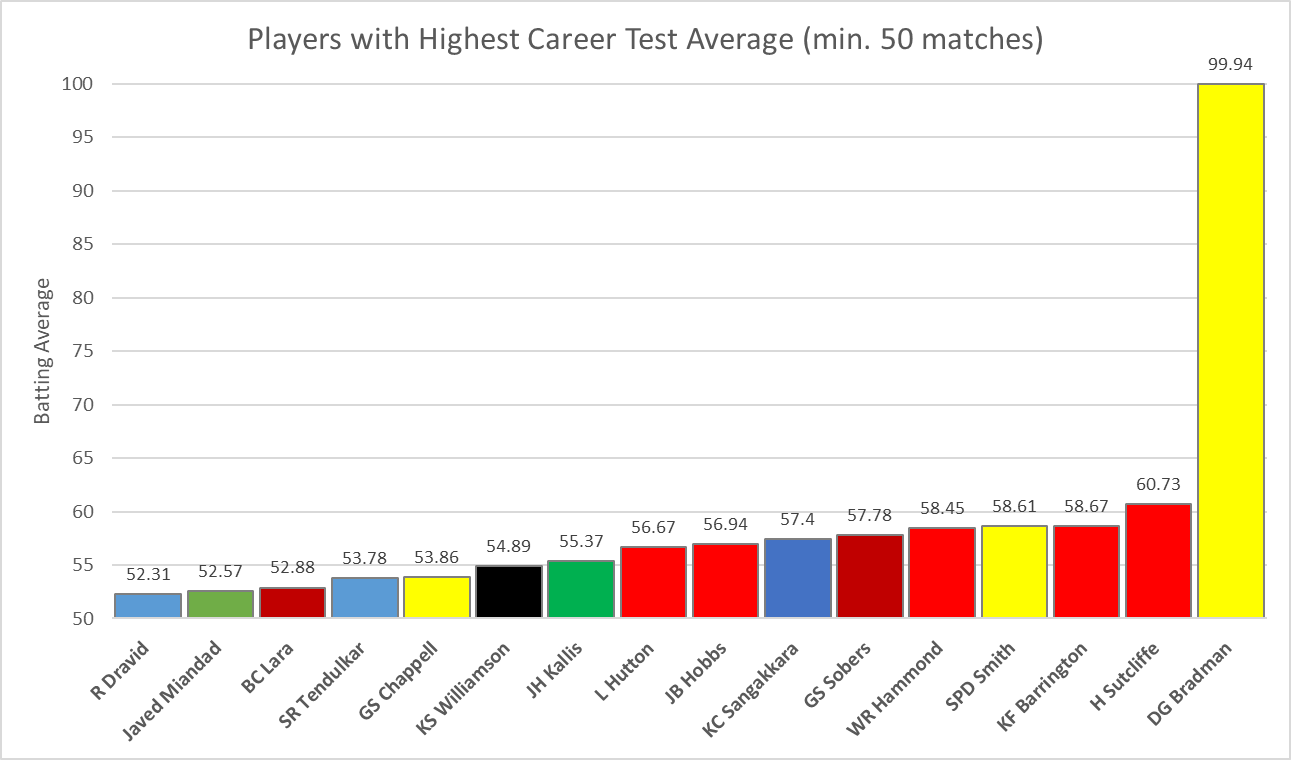

It hurts the brain honestly. On top of that, many of the players in the top end of that chart had very short careers, even by the older era standards. Bradman played 52 test matches, whereas Pollock only 23! We’ve seen in other athlete discussions how longevity typically cruels productivity, so let’s get rid of the players who had success for a short period and not much else by shifting the requirement for the chart to 50 or more tests played:

Goodness gracious.

And now let’s shuffle everyone along and bring in some players:

Okay, now we’re talking. That graph right there is almost every player to have played 50 or more tests and still average above 52, Younis Khan and Mohammad Yousuf of Pakistan didn’t quite make the chart but have averages of 52.05 and 52.29 respectively. The gulf from 1st to 2nd place truly is insane, especially considering how gradual and as expected the progression up until 2nd place is.

Now, to get a sense of how massive an outlier this is compared to other statistical outliers, I wanted to compare it to other sports. The thing we’re comparing here isn’t championships, or contributions to the team in some tangential way, it’s just straight up scoring. And not even total scoring by playing for a long time, we want to look at how good a player is at scoring per game played.

So, I looked at points per game for basketball and rugby players, goals per game for hockey, soccer, and AFL players, tally points per race for F1 drivers, % of matches won for tennis players in opens, touchdowns per game for NFL players, and of course batting average for cricket and baseball players. For all of these different sports I tallied the top 10 people for each category and what the average was across that top 10. I then calculated how far in front of that average the best and 2nd best person was. The difference between these two illustrates how far ahead the number 1 player is.

For example, with basketball, Michael Jordan’s points per game (30.12) is 9.5% above the average of the 10 best, but the next best is Wilt Chamberlain (30.07) who is 9.4% above that average. So the best is only a fraction better than the second best, unlike Bradman as we can see in that chart above who is so, so far ahead of the second best. For each sport I chose the highest level of major competition. Could any of the other sports provide a best player that far or further ahead of the next best? Well, no…

The best and second best for each of the categories are:

NBA points per game:

1st, Michael Jordan - 30.12

2nd, Wilt Chamberlain - 30.07

NHL goals per game:

1st, Wayne Gretzky - 1.92

2nd, Mario Lemieux - 1.89

NBA points per game:

1st, Michael Jordan - 30.12

2nd, Wilt Chamberlain - 30.07

Association Football goals per game:

1st, Erwin Helmchen - 1.71

2nd, Fernando Peyroteo - 1.62

Test Rugby points per game:

1st, Dan Carter - 14.27

2nd, Andrew Mehrtens - 13.81

NFL touchdowns per game:

1st, LaDainian Tomlinson - 0.95

2nd, Shaun Alexander - 0.91

MLB batting average:

1st, Ty Cobb - 0.366

2nd, Oscar Charleston - 0.365

F1 points per race:

1st, Lewis Hamilton - 14.03

2nd, Max Verstappen - 13.86

Tennis Opens win percentage (men or women):

1st, Margaret Court - 90.1%

2nd, Steffi Graf - 89.7%

AFL goals per game:

1st, Peter Hudson - 5.64

2nd, John Coleman - 5.48

Test Cricket batting average (min. 20 matches):

1st, Don Bradman - 99.94

2nd, Adam Voges - 61.87

I then subtracted the second best from the best and expressed that as a percentage of the top 10 average. Now, that’s hard to get a grasp of reading through like that, and without the rest of the top 10. So check this out:

So Bradman’s cricket dominance isn’t just impressive for being so far ahead of his peers, it’s also a complete anomaly in sports. In all other codes the very best scorer of all time is only a few percent ahead of the next best, Bradman really is the statistical outlier of all outliers. The other fascinating thing is how few of the all time scorers across the sporting world are from this century. People speak of sports getting bigger and faster, more extreme and competitive, but in almost every one I looked at the peak scoring was happening decades ago, with Hamilton and Carter the exception (Gretzky and Jordan really dominated in the 90s, and LDT in the 2000s).

So let’s look at how a few of the top test average batters performed throughout their careers:

That last one illustrates why the average axis had a maximum of 400, in 1932 the Don played only 2 tests, in which he scored 402 runs for just one dismissal so his average was bonkers. But as we can see looking at those different legends of the game, all players have a combination of good and bad years. Sangakkara, Sobers, Smith, Sutcliffe (I didn’t intentionally select just S named cricketers, but wow, there you go) all had at least 3 years with averages below 50 and (except for Smith) 1 year each with average above 100. Bradman on the other hand only had a single year with an average below 50, and 7 of his 13 years of cricket averaged above 100!

Let’s take all those careers shown above and combine them on one graph:

Yeah that’s not super handy, let’s change from average per year to cumulative average throughout their career:

There we go. So we can see that Sutcliffe started with an average of 80 for his first 4 years before falling to more mortal levels. The other S cricketers had a more conventional trajectory, building to their peak around 5 to 6 years in their career. Bradman on the other hand just kept on climbing, and once passing an average of 90 never again dipped below that mark.

But the truly stunning thing about Bradman is the fact that he lost so much time to the Second World War but still set records. Check out if we separate his career graph into chronological years not sequentially as played:

The two calendar years before WW2 he averaged 138 and 108.5, and the two after he averaged 210.5 and 65.3. This is nuts to consider, he has the career total records for a bunch of things, but because he only played 52 test matches he lost the career records for 50s, 100s, and total runs. Imagine if he’d had these extra 7 years! Based on his career numbers those years would have represented around another 30 tests, and assuming his average (and other ratios) were consistent this would mean an additional 17 centuries, 11 double centuries, and 4,600 runs. This would put him 4th all time for centuries (and wayyyyyyyy out in front of the double centuries list) though he would still only just crack the top 10 list for most runs. That’s the thing about Bradman’s era, they didn’t play many test matches. For one thing there were only a handful of cricketing nations playing test matches, and the other, touring was a huge deal, with weeks and weeks spent onboard ships. Bradman played more than 5 tests in a year only 3 times, and never more than 8. By comparison Steve Smith has played more than 5 tests in a year 8 times in his career, and for 6 of those he played 11 tests in the year!

But let’s focus on what he did score in those 52 tests played. He scored 6,996 runs, 29 centuries, 12 double centuries, and 2 triple centuries. Many of the surrounding statistics of these totals are still records to this day. Here are some of his records:

Highest career batting average (as we’ve explored in depth)

Most double centuries

Highest conversion rate of 50s to 100s

Most scores 250+

Highest batting average in a test series (also 2nd highest and 6th highest)

Most runs in a days play (also the 5th and 7th most)

Most runs in a series

Highest rate of 100s per innings

Highest rate of 200s per innings

Highest ratio of team’s runs scored over career

Only player to score 3 double centuries in a series

Most consecutive matches with a century

Fewest innings to reach each 2000, 3000, 4000, 5000, and 6000 test runs

We know his batting average record is truly unbreakable (arguably more than any other in all of sport), but what about these other ones? Let's step through some of them.

First, runs and batting average in a single test series. For the former, only 9 times in history has a player managed 800 or more runs in a series. Of those 9 occasions, 3 were Bradman… The other 6 were all by different individuals, though only 3 cricketing teams have produced batters capable of 800 or more in a series, the West Indies, England, and Australia:

Keep in mind that the number 1 spot was a 22 year old Bradman, not even playing at home (he was touring Britain), and in only his second ever test series!

For test series average, on 16 occasions a player has averaged 125+ over a test series (while playing in 4 or more tests, don’t want a 2 test series where someone goes large to skew the results, we want sustained success after all). Bradman accounts for 3 of those, again the only person appearing more than once on the list. If we get a bit more lax and make it a series averaging 100+, suddenly the number of occasions jumps to 48! It’s a big leap from averaging 100+ to 125+. That list of 48 has several batters with multiple instances of achieving 100+, though Bradman still has the most. Back to 125+:

First off, wow, that’s a big margin from Bradman to Bradman, though Kallis almost pipped Bradman for second spot behind himself. The other takeaway is go Australia, even without Bradman they would have the most spots on the graph.

Okay, for both runs in a series and average in a series I think we can safely put those records in the unbreakable basket. What about centuries, multi-centuries, and conversion rates?

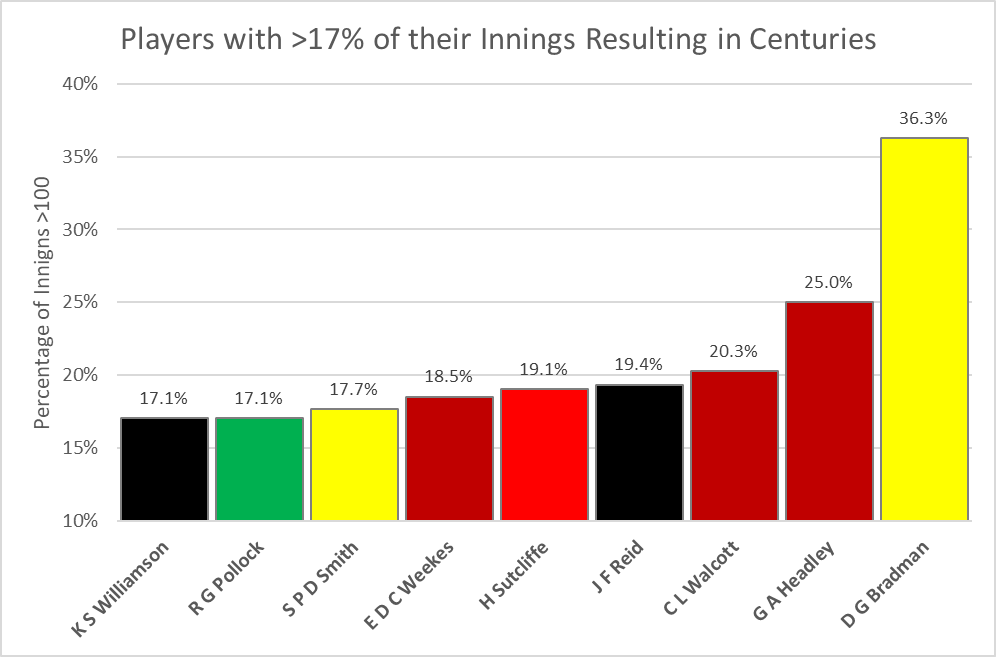

Well, Bradman scored 29 centuries, which puts him a long way down the list for most centuries (16th). The top spot, Sachin Tendulkar, has a whopping 51 centuries. But, Bradman only played 52 tests, compared to Tendulkar’s 200 (what?!). So let’s look at the number of centuries as a percentage of innings played. For that, 26 players have a ratio of 15% or better, Tendulkar’s by the way is 15.5%. Let’s narrow it down and adjust the threshold to 17%, that little change of 2 percentile drops our players down to 9:

Here the West Indies have the most representatives, but gosh Bradman’s numbers are again unreachable. Also, the previous few figures have contained solely retired players, here we have our first contribution of the current generation, with Williamson and Smith showing respectable ratios of centuries per innings, even if they’re less than half of the Don…

So, with that graph in mind it should be no surprise that he also has the best conversion rate of half centuries to centuries. What’s interesting is that it’s not nearly as dominant as the previous records. Here are all 11 players in the history of the game who convert a 50 to 100 on 50% of the time or better:

This one is interesting, only Walcott, Headley, and Bradman from this list are also in the top 15 of batting average. This is because if you score very little most of the time, but when you do crack 50 you go big more often than not, you’ll have a small average but high conversion rate. It makes it all the more impressive that Bradman and Headley dominate this statistic while also having incredible averages. This is probably one of the more breakable records, though the closest player from the previous 50 years is Dhawan, who is at the end of his career and hasn’t played a test in 5 years.

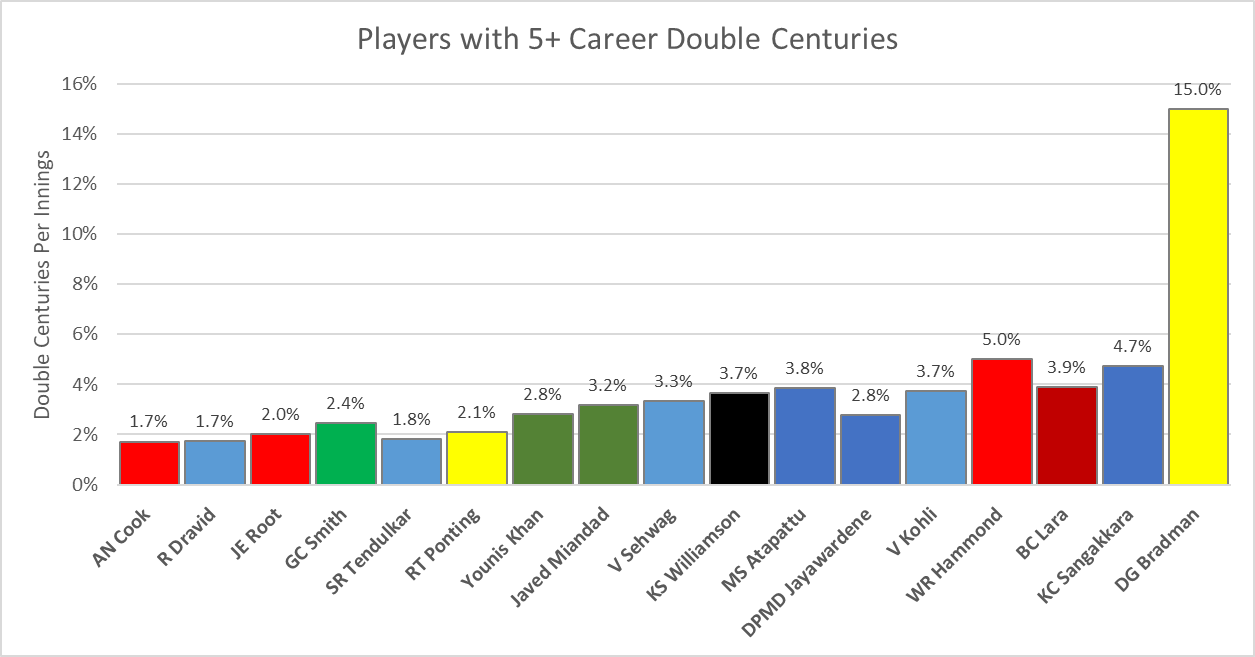

Now, the truly mind blowing stats, double centuries. Despite playing only 52 tests Bradman has the most double centuries. Ever. Scoring double tons is rare, to manage it 5 times in a career, that’s only been done by 17 individuals:

Ooh, narrow margin here for the Don for once. Also, while the Indians and Sri Lankans might not have many representatives in the top 10 batting average list (none from India) they certainly know how to go large, with the two countries providing 7 of the 17 batters to post 5 career doubles. But, that narrow margin is because Bradman played less than half the tests Sangakkara did. Let’s take number of matches played into consideration and adjust that graph from total double centuries to rate of double centuries per innings played:

Okay yeah, now that’s unbreakable. Bradman scored a double century in 15% of his innings! When you watched him walk to the crease there was better than a 1 in 7 chance he was going to crack 200, that is truly insane. In terms of double centuries in a test series, he’s the only one to score 3 in a series, and while 13 players have score 2 in a series, only Clarke, Hammond and Bradman have done that more than once, with Clarke and Hammond achieving it twice each, but Bradman did it in 4 separate test series!

Then there’s stringing together a run of form. In the history of test cricket a batter has cracked 100 in 4 or more consecutive matches a total of 20 times. Most of those were a one off feat, though Kallis, Hayden, and Barrington have all done it twice, and Bradman thrice. But 5 or more in a row? Only Kallis, Yousuf, Gambhir, and Bradman have done that, with Bradman’s streak extending to 6, a feat no other has equalled.

Now, we’ve talked about double centuries, but what about triple centuries? Well, first off, there have only been 31 in the game’s history, but even more rare are players to crack 300 more than once. That has only been achieved by 4 players: Lara, Sehwag, Gayle, and Bradman. But Bradman was once on 299 not-out when his last partner was dismissed and he was left stranded, a single run shy of being the only player with 3 triple centuries. This illustrates that while he has to share the 300 club record, if we instead make it the 250 club he stands alone. 250+ has been achieved a lot more than 300+, with 99 players in history achieving it. 18 of those players managed it on more than one occasion:

Again, only a margin of 1 between Bradman and Sehwag, maybe the record for 250+ scores is breakable. Aslo, interesting how India dominated the double century list but only have one player with multiple 250s, apparently Dravid, Kohli, and Tendulkar are happy with 200 and don’t feel the need to press on. Now, like the double centuries, let’s adjust these numbers for innings played:

There we go, that’s more like it. Someone might one day score more 200s or 250s than the Don, but no one will score them at 15% and 6% respectively, it’s truly remarkable.

Now, I know we’ve covered a lot of stats, but bear with me, there are two more cool ones to explore. First, an interesting one that I hadn’t considered until I started researching this piece, which is the proportion of the team’s runs a single player scores over their career.

So, you’re the star batter, you’re expected to score a good chunk of your team's runs, and you more or less achieve this over your career. What’s a typical percentage of the team’s output that you accounted for over that span? Well, I can tell you! Since test cricket has been played, a total of 47 players have managed to score 15% or more of their team’s runs. Considering there are 11 players who can add to the total, but that usually only the top 6 or 7 contribute significantly, this number feels about right. Only 2 players managed to account for 20% or more of their team’s runs throughout their careers, George Headley (21.38%) and Don Bradman (24.28%). Nearly a quarter of the runs Australia scored from Bradman’s debut to his retirement were from his bat!

Though, I must say, looking at the list of players scoring 15% or more, many of these had short and productive careers, which makes sense, it’s hard to be so consistent over a long career. If we add a qualifier, say, you have to have played 50 tests, then the number drops from 47 players to only 29, and no one cracked 19% other than Bradman. The number drops to 15 if the threshold is moved only 1% to more than 16%. The most impressive in my mind (apart from the Don of course) is Brian Lara, who managed 18.87% of the West Indies runs over a career spanning 131 tests! Here’s the list of players to account for 16% or more of their teams runs playing 50 or more tests:

This is also very unbreakable by the way.

Finally, I want to talk about run rate. Many fans assume that batters in the modern game must have much higher strike rates (runs scored per ball faced) due the rise of shorter formats. After all, if a player is used to playing T20s and One Day matches, surely their test batting will be at a more ferocious pace also. Now, we have seen this in patches, and it does feel more and more like there are specialist test batters who can be aggressive or defensive. So, at least personally, it feels as if batters from the past must have had sluggish run rates. This is certainly not the case with Bradman. Keep in mind, in his era minutes at the crease was more closely monitored than balls faced, and scoring quickly in a day’s play as opposed to a given number of overs was often the mark of a quick strike rate.

So let’s look at runs in a day’s play. In the history of the game, 49 players have scored 200 or more runs in a single day’s play. The most recent occurrence was in 2019, when Agarwal scored 206 in a day for India against Bangladesh. All up it’s happened 22 times this century, with the 2000s being the most prolific of all decades (13 times), and the 2010s the third most prolific (9 times), which would back up the assertion above. However, the second most prolific was the 1930s (12 times), though 9 of those were from two men, Bradman and Hammond. You see, of the 49 players to achieve this feat, only 7 have done it more than once. Of those 7, only 2 have done it 4 or more times, Hammond with 4, and Bradman with 6. Six times! On six different days Bradman scored a double century or more in a single day’s play. I mean, many of the greatest batters in history don’t even have six 200s to their names, let alone scored in a day. It’s frightening. He’s also the only player ever to score 300 in a day's play. Honestly, that’s hard to get my head around. Also, utterly unbreakable (both the 300 in a day and also the 6 occurrences of 200+ in a day).

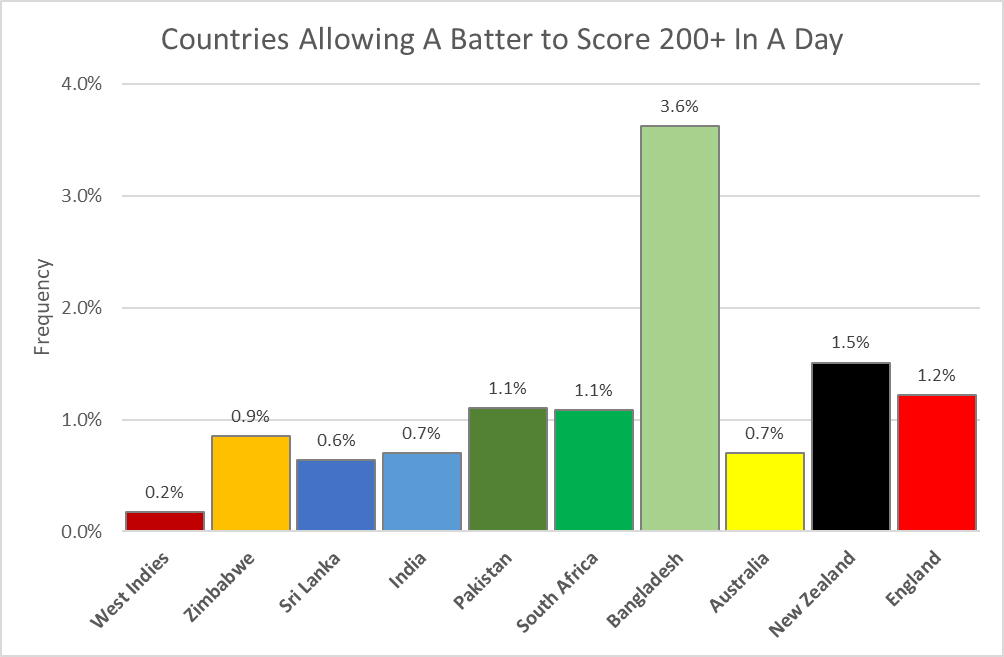

Fun side fact to come out of this, I tallied the 200s scored in a day by which test team allowed said flurry of scoring, and it looks like this:

Mostly I just wanted to include this to make fun of England. But then, they have played by far the most tests, and 3 of those 13 were by Bradman alone. Let’s make it as a percentage of tests played by the team:

Okay, England are still in the top 5, but not as bad as New Zealand and nowhere near as bad as poor old Bangladesh. As an Aussie this graph is great, as the two great rivals (England for cricket, New Zealand for rugby) both come off looking poorly.

Back to Bradman and strike rate. Now, you could be thinking, “Jacob, they might have bowled a lot more balls back in the day, maybe scoring 250+ in a day was easier, I mean less fast bowlers with their crazy run-ups, surely?”. And you’d be right in general, overs and balls bowled per day have dwindled over the years, to the point where the ICC applies heavy fines and sanctions for teams bowling at slow rates. So let’s just look at strike rate. Here is that list of test batting average (minimum 50 matches) again:

Gosh I love looking at that. But back to the point. Let’s adjust that graph to instead show strike rate, runs scored per ball faced over a career:

What?! Only Lara, the legendarily aggressive batter, has a higher strike rate than Bradman, and it’s barely higher. If we look at the next 15 best batting averages only Ponting (also 0.59), Hayden (0.60) and Viv Richards (0.7) are higher than the Don. Actually that number for Richards is crazy, what a legend. But Bradman is an outlier. In that graph above, all the English batters were within a generation either side or concurrent with Bradman, and as you can see their strike rates were much lower than the modern greats, and way behind Bradman. But, the idea that Bradman couldn’t succeed in the modern game is hilarious. He had a test strike rate like Lara and never got out! If he had been born in 1988 instead of 1908 he would right now be the number batter in tests, ODIs, and T20s.

He also scored quickly in terms of runs per match (clearly, his average is bonkers), in that he has the record for fewest innings required to reach 2000, 3000, 4000, 5000, and 6000 runs, and had he scored the measly 4 runs needed off his last test, would also be fastest to 7000 runs.

So, will his records fall?

I think you’ve probably guessed the answer to this from our discussion so far.

No.

I mean, maybe a few. Most 200s, most 250s, these might, just maybe, fall. Someone might also equal or exceed his 3 double centuries in a test series. But all of these are very unlikely. Whereas 200s and 250s per innings, as well as 100s per innings, 100s per 50, runs in a day, runs in a series, average in a series, innings required to reach each multiple of 1000 runs (up to 6000), percentage of team runs over a career, and most of all career batting average, these are all utterly unbreakable.

The thing is, it’s not like the game has changed to make them unbreakable either. Everything since Bradman’s era has only gotten better for batting. Pitches are covered when it rains so they don’t deteriorate as much, batters have protective equipment so they aren’t as impacted by aggressive bowling, bats are much wider and thicker so more shots reach the boundary, laws have been introduced to restrict where bowlers can legally bowl the ball, and modern athletes have all the advantages of 21st century conditioning, nutrition, and sports science. Yes bowlers have gotten better on the whole, there were some frightfully good bowlers in every era, but all analysis shows that on average bowling (particularly fast bowling) is much harder to face now than it was 100 years ago. But the batters have never had better tools to face them with! Modern batters play an insane amount of cricket and with the best conditions ever to bat in, and yet no-one has come within distant reach of Sir Don Bradman.

Bradman was not some product of a particular era of the game that fostered or enabled his dominance. He was just genuinely exceptional, the statistical outlier that millennia of billions of human DNA permutations was bound to create eventually. There have probably been people born who would be as freakishly incredible at other sports, it’s just the likelihood of them being born in an era or location where they can use this talent is low. There might have been some peasant in the Mongolian empire in 1258 who would have been the best lawn bowls player the world has ever seen, but the sport hadn’t been invented yet. We’re just lucky that the outlier of cricket was born in a cricket playing nation in an era when the game thrived.

Don Bradman’s exploits will never be equaled again in test cricket, players today will just have to aspire for 2nd place, fighting for the honour of being the best since Bradman.

Bradman in 1998 with his two favourite active players at the time, Warne and Tendulkar. He was 90 years old here. Also a neat crossover from my previous article. Picture taken from here

Here are some highlights from the Don, batting in the 1930s and 40s:

Footage edited from source here

Bonus record!

Congrats for reading through till here, you are an absolute legend. To reward your perseverance I have a bonus record for you. Did you know that Donald Bradman took test match wickets? He wasn’t known as an all-rounder (not even slightly), but he did bowl 20 overs in his career, taking 2 wickets at an average of 36. Now, this is not a good average for a bowler, but for many all-rounders it’s not too shabby. Check out four of the best all-rounders (by common consensus) in the history of the games test bowling statistics:

Ian Botham (England): 383 wickets at 28.40

Kapil Dev (India): 434 wickets at 29.64

Garfield Sobers (West Indies): 235 wickets at 34.03

Jacques Kallis (South Africa): 292 wickets at 32.65

Now those last two are considered the greatest all-rounders to play the game, and their bowling averages aren’t that much less than the Don managed in his very few attempts at rolling the arm over. That said, Sobers and Kallis are remembered as batting all-rounders, as they have some of the best batting records of any player let alone all-rounders. Not as good as the Don though…

You see, often an all-rounder is judged by weighing up the net contribution to the team, if their batting average is much higher than their bowling average then they are scoring more runs than they are allowing, which is a net advantage. This is a tad simplistic, but does go a way to showing the all-rounders career impact with bat and ball. Check it out:

Ian Botham (England): 5,200 runs at 33.54

Kapil Dev (India): 5,248 wickets at 31.05 (only player with >5,000 runs and >400 wickets)

Garfield Sobers (West Indies): 8,032 runs at 57.78

Jacques Kallis (South Africa): 13,289 runs at 55.37 (only player with >10,000 runs and >200 wickets)

I mean Sobers and Kallis have better batting averages than Ricky Ponting, Sachin Tendulkar, heck pretty much any batters from the past 50 years who played 50 or more tests, expect Sangakkara and Steve Smith. Seriously, players who’ve played in the past 50 years and at least 50 test matches, Sobers and Kallis are the 3rd and 4th highest batting averages, much more batters than all-rounders!

Ok, so let’s look at batting average minus bowling average to see how useful a net contribution these players were over their careers:

Ian Botham (England): Batting Ave. - Bowling Ave. = 33.54 - 28.40 = 5.14

Kapil Dev (India): Batting Ave. - Bowling Ave. = 31.05 - 29.64 = 1.41

Garfield Sobers (West Indies): Batting Ave. - Bowling Ave. = 57.78 - 34.03 = 23.75

Jacques Kallis (South Africa): Batting Ave. - Bowling Ave. = 55.37 - 32.65 = 22.72

Wow, Kallis and Sobers numbers are very impressive compared to the other two. And by the way, no other player in history can edge Kallis or Sobers (numbers as of November 2023):

Wally Hammond (England) = 20.65

Imran Khan (Pakistan) = 14.88

Kieth Miller (Australia) = 14.00

Steve Waugh (Australia) = 13.62

Ravindra Jadeja (India) = 12.34

Shaun Pollock (South Africa) = 9.20

Steve Smith (Australia) = 5.56

Ben Stokes (England) = 4.34

That list isn’t exhaustive, just representative, also only includes players with 50 or more tests. Some of them aren’t even all-rounders, not really, just batters with very good batting averages who took some wickets as well, especially true for Waugh, Smith, even Hammond. You see where I’m going with this? Bradman could have had a bowling average of 70, which would be the worst bowling average in the history of the game (amongst players with 50 or more tests matches), and still have an batting/bowling average differential superior to Sobers and Kallis. As it is, his respectable average of 36 gives him a differential of 63.94!

The thing is, this is also unbreakable, because even if someday a bowler is so deadly, so economic, that they average better than any bowler ever, say single figures, they would still need to have a batting average in the 70s! Better than any legendary batter the game has produced bar Bradman. So yeah, he is officially the best all-rounder the game has seen as well. Here are the only 11 players in history to play 50+ matches and have a batting - bowling average differential greater than 10:

Alright, that’s enough. We get it, Bradman is great.

Thanks everyone, see you next time.